In a new study, researchers at Lawson Health Research Institute (Lawson), Western University and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) have found that specialized programs for early psychosis can substantially reduce patient mortality.

Published in The American Journal of Psychiatry, the study examined health administrative data for patients treated between 1997 and 2013 at the Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychoses (PEPP) at London Health Sciences Centre. PEPP was founded in 1997 as the first early psychosis intervention (EPI) program in North America. EPI programs, which have been rolled out across Ontario, are specialized care models that focus on early detection of psychosis to provide intensive treatment during the first two or three years of illness.

“An episode of psychosis is characterized by delusions and hallucinations, as well as disorganized thought and behaviour patterns,” explains Dr. Kelly Anderson, lead researcher on the study, a scientist at Lawson and ICES, and an Assistant Professor at Western’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry. “Evidence shows that early treatment of psychosis, from the first symptoms or episode, is very important in improving long-term outcomes.”

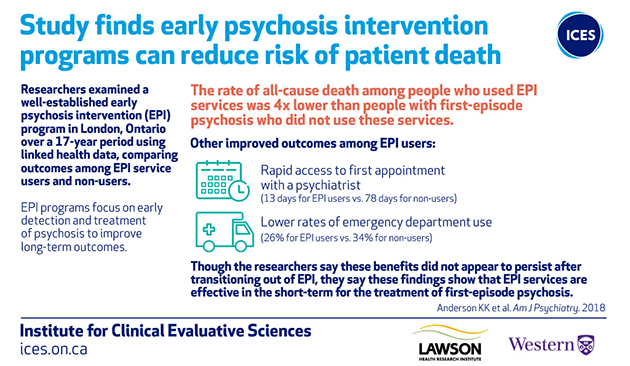

The study compared early psychosis patients at PEPP against those who were not treated through an EPI program. The research team studied patient outcomes within the first two years after diagnosis. They found that patients being treated at PEPP experienced a four-fold reduction in risk of mortality, compared with people with early psychosis receiving services elsewhere.

In addition, patients at PEPP had rapid access to their first appointment with a psychiatrist and their psychiatrist visit rates were 33.2 per cent higher than the non-EPI user group. They also experienced an 8.7 per cent reduction in emergency department visits and fewer involuntary hospitalizations.

“The aim of our study was to examine the ‘real-world’ effectiveness of EPI programs in the context of the Ontario health care system,” says Dr. Anderson. “Our results indicate a number of beneficial outcomes associated with EPI programs. Most importantly, the risk of mortality is significantly reduced.”

Previous research has shown that mortality is at least 24 times higher in the first year after diagnosis of a psychotic disorder when compared to the general population. Dangerous behaviours, medical co-morbidities and suicide are all potential factors.

The study also found that patients being treated at PEPP had lower rates of primary care visits and higher hospitalization rates overall. The researchers point to a need for more collaboration with primary care providers to reduce risks of co-morbidities associated with psychotic illness and anti-psychotic medications, such as weight gain and sedentary behavior. They also point to the need for additional research to understand higher hospitalization rates.

“Hospitalizations are often a necessary therapeutic intervention for patients with psychotic illness,” says co-author, Dr. Paul Kurdyak, a scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) and ICES. “While our study suggests that overall hospitalization rates are higher among EPI users, it also suggests involuntary hospitalization rates are lower. It may be that EPI users have better access to in-patient care and are more willing to seek care when needed.”

In addition, the research team examined patient outcomes from three to five years post-admission, when patients have typically transitioned from intensive EPI services to management by their psychiatrist. Many of the benefits associated with EPI programs were not observed after three years when compared to patients who did not receive EPI services, although EPI patients were still more likely to see a psychiatrist.

“We may be seeing fewer benefits long-term for a number of reasons,” adds Dr. Anderson. “While there is a reduction in intensity of EPI services at this time, there may also be improvements in individuals not treated through an EPI program due to the natural trajectory of psychotic illness. There are currently clinical trials being conducted worldwide to study whether the length of EPI programs should be extended.”

Dr. Anderson hopes to expand her research beyond London to confirm the findings across the province. “We’re fortunate that the Government of Ontario has invested heavily in the EPI model of care,” says Dr. Anderson. “Our findings show the ‘real-world’ benefits of EPI programs and also suggest clues on how we can make EPI programs even more effective in the future.”