In the operating room, just before surgery begins the last face a patient sees and last voice they hear is that of the anesthesiologist. While surgeons rarely hand over care during a procedure to another surgeon, anesthesiologists do occasionally transfer care to a colleague after a surgical procedure is under way. A new study from Lawson Health Research Institute, Western University and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) Western site in London, Ontario examines the operating room practice of handing over patient care between anesthesiologists.

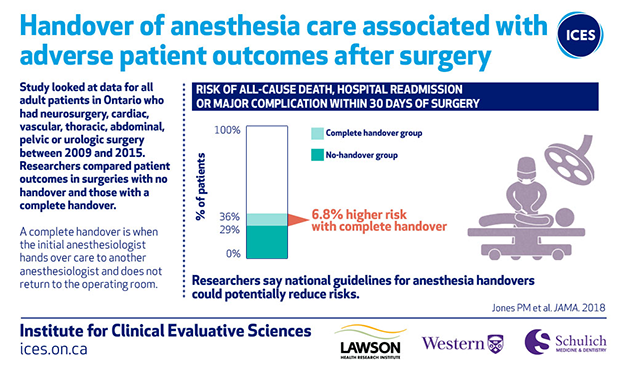

The retrospective, population-based study, published in the journal JAMA, examined the postoperative outcomes of 313,066 adult patients undergoing major surgeries. The researchers compared patient outcomes in surgeries which did not experience a handover of anesthesia care with those where the primary anesthesiologist transferred care to a colleague and did not return to the operating room.

“Patient handovers occur for a variety of reasons, including illness or fatigue, to comply with working hour policies, or simply to balance an individual’s work hours and personal commitments,” says Dr. Philip Jones, Lawson scientist, and associate professor, Department of Anesthesia & Perioperative Medicine and Epidemiology & Biostatistics at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry.

The cases examined as part of the study were of all patients in Ontario who had a surgery expected to last at least two hours and required a hospital stay of at least one night between April 2009 and March 2015. Researchers included patients undergoing a broad group of surgeries including neurosurgery, cardiac, vascular, thoracic, abdominal, pelvic and urologic surgery.

“Amongst anesthesia doctors, there has always been an assumption that handovers were ‘care neutral,’ in that they would not harm patients as long as sufficient information was communicated between anesthesiologists,” continues Dr. Jones. That assumption, combined with on-call scheduling practices that have resulted in shorter working hours, is likely a factor in the observation that handovers progressively increased in each year of the study, reaching 2.9 per cent of all major surgeries studied in Ontario in 2015.

“Our study finds that our assumptions of ‘care neutrality’ may be wrong and that, among adults undergoing major surgery, complete handover of intraoperative anesthesia care compared with no handover was associated with a higher risk of adverse postoperative outcomes. Our results are also congruent with work done by other research groups, heightening our concern about this practice,” explains Dr. Jones.

An adverse outcome (major complications, hospital readmission, and all-cause death) occurred in 29 per cent of the no-handover group and in 36 per cent of the complete handover group. On average, for every 15 patients exposed to a complete anesthesia handover, one additional patient would be expected to experience an adverse outcome.

The findings may support limiting complete anesthesia handovers or creating an improved system of anesthesia handovers. “What this study suggests is that we need to pay careful attention to patient handovers. A national consensus statement describing the appropriate circumstances for anesthesia handovers to occur, that also incorporates best practices in communication, would be a helpful start to reduce the risks associated with these handovers,” concludes Dr. Jones.